Git is one of the most useful tools out there for developers. It improves team collaboration and speeds up the working process, as it allows you to store code, track changes, and revert to previous versions of your project. If you haven’t used Git yet, keep in mind that it might seem a tiny bit difficult in the beginning. But, once you get familiar with it, you’ll notice it’s easy-peasy-lemon-squeezy. Kinda like everything in life, but more on that in a different article.

Git’s Definition

By the book, you can define Git as an Open Source Distributed Version Control System. And, as this wordy definition might not be really helpful, let’s break it down and see what every part stands for:

- Control System: this is how you can tell that Git is a content tracker. One of its main purposes is to store content, which 99% of the time is code.

- Version Control System: the code stored in Git is constantly changing and an increasing number of developers are adding code at the same time. Considering this, it’s useful to have a history of everything that’s been going on. And that’s where Version Control System steps in.

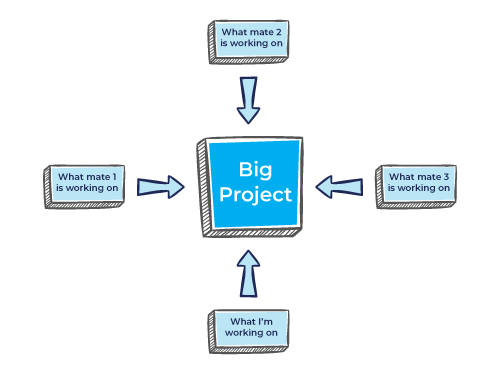

- Distributed Version Control System: Git has a remote repository, stored in a server, and a local repository, stored in each developer’s computer. This means that each developer has a copy of the code on their own computers. The local repository is where a developer makes any changes, tests, experiments, without interfering with the other developers working on the same project. The remote repository is where the final version of the code is shared with the rest of the world (or just your team). To better visualize what I’m saying, take a look at the illustration below:

Hopefully, I managed to break down what Git is understandably for someone aspiring to work in the tech world. But, is this how you would explain Git to your 5-year-old self? I’m guessing no. Unless you knew what “code”, “repository”, or “developer” meant back then. In that case, hats off to you.

Explaining Git To Your 5-Year-old Self

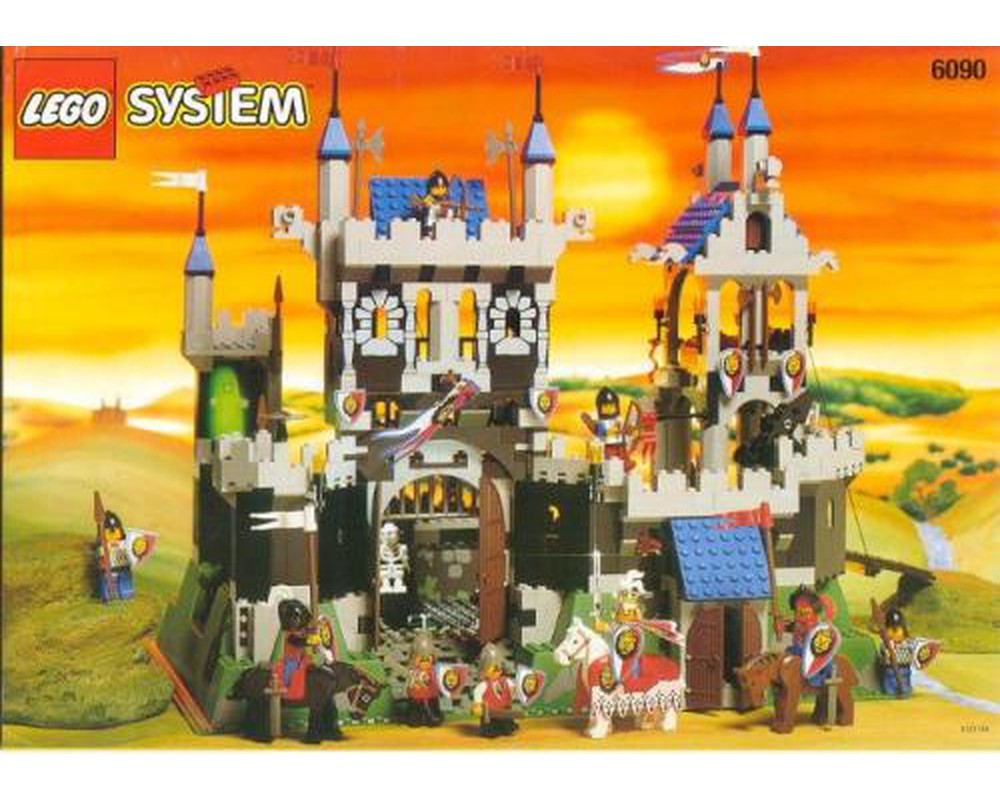

Scenario: you’ve just been dropped off at kindergarten and you meet up with your friends. You get ready to start playing with the toys you brought from home when one of your mates shows you their new Lego set. It’s the Lego Royal Knight’s Castle, one of the most popular Lego sets back in the 90s. Together with 4 of your friends, you form a group and decide to start working on it. You wonder if it’s better to work together on every part of the castle or work individually on some of the parts and put them together when they are done.

At first, you start working on the Lego set at once. Nobody wanted to work separately on the parts, as you wanted to do everything together. As fun as this sounded in the beginning, after the first 20 minutes you notice you’re not actually getting anywhere. You can’t decide how to start assembling the castle because all 5 of you want to be involved in every part of the process. You sense your method might be a bit inefficient. The castle can’t be built by all of you at once.

So, you take the lead and propose a new plan. Each kid gets one part of the castle and works on it individually. When the parts are done, you’ll quickly assemble the castle. As you’re doing this individually, there’s nobody around to tell you if you’re doing something in a right or wrong manner. When everyone completes their parts, you’ll notice if each of you did the job properly. If the castle can be assembled, it means you’ve completed the project. You did your part good! Otherwise, you have to take your part back and start working on it again.

This is how Git works too. You have the local repository, the place where you work on your part. Then, you have the remote repository, where your team is putting what they’ve been separately doing on their own local repositories together. And this is how other Distributed Version Control Systems work too.

Final Thoughts

As projects have more developers working at the same time, systems such as Git provide a safe space to work on. It ensures there are no code conflicts between developers, it allows you to go back to previous versions or track any code changes, and it facilitates the team’s overall workflow and collaboration.

If you’re making your first steps in the developing world and want to have a head start, experiment with working on Git. Or on a similar Distributed Version Control System such as Mercurial or Bazaar. You can download Git and get started with it from here.

Another thing you can test is working on Centralized Version Control Systems or Local Version Control Systems. The Distributed Systems mix the best of both worlds as in a Centralized System you don’t have your local repository to work on and on a Local System the remote repository is missing. If you’re a Computer Science student, you’ve most probably already experienced working on a Local Version Control System.

As there are more options available, it’s up to each team to decide what working style fits them best. Usually, the battle is between Distributed and Centralized. An example of a Centralized Version Control System is Subversion. To learn more about Distributed and Centralized Systems, check out this 2-minute insightful and on-point video.

The article was written by Ruxandra Mazilu

[/fusion_text][/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]